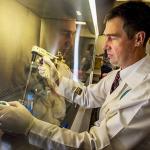

Dr. John Schieffelin

Assistant Professor of Medicine & Pediatrics, Sections of Pediatric & Adult Infectious Diseases

Biography

Dr. Schieffelin devotes a significant amount of time to the laboratory. His research focuses on the natural history, clinical care and immunology of viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs). Currently he is involved in both basic science and clinical research on Flaviviruses, such as dengue and Zika, as well as Lassa fever virus and Ebola virus. His laboratory studies how antibody-virus interactions can have both protective and pathogenic effects.

He has a broad background in clinical infectious disease, immunology and virology and international clinical research and capacity building. As an Adult and Pediatric Infectious Disease Fellow, he developed expertise in generating and characterizing human monoclonal antibodies and carried out research on the mechanism of action of neutralizing and enhancing antibodies against dengue virus. As a junior faculty member, he has been Co-Investigator on several NIH-funded grants and contracts investigating Lassa fever. This research has laid the groundwork for the proposed work by developing necessary clinical and laboratory infrastructure and data collection tools. In addition, it established strong ties with the staff of the Sierra Leone National Lassa Fever Program. He has successfully administered the projects (e.g. staffing, human subjects protections, budget), collaborated with a diversity of other stakeholders, and produced several peer-reviewed publications with several more in preparation. During the Ebola Outbreak, he served as a consultant to the WHO Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network in Sierra Leone participating in both clinical care and local staff training.

In addition, he is actively involved in NIH-funded research projects in Kenema, Sierra Leone where he oversees human subjects research on VHF diagnostics development and the natural history and long-term sequelae of Lassa fever and Ebola virus. The long-term goal of his research program is to develop and test new supportive care and therapeutic strategies for VHFs.

Education

Louisiana State University, Health Sciences Center & Tulane University

Tulane University

Tulane University, School of Medicine

Links

Articles

Being Ready to Treat Ebola Virus Disease Patients

An unprecedented number of health care professionals from a variety of clinical settings, in a wide range of countries are thinking about, preparing for and caring for Ebola virus disease (EVD) patients. Guidance documents on infection prevention and control (IPC) practice and clinical care have been produced by organizations with EVD experience.1–3 The World Health Organization (WHO) produces guidance for implementation across a wide range of resource settings. Medecin Sans Frontières produces guidance for medical team activities across the outbreak. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) focus on measures which can be taken by the United States health system and extrapolated by others involved in preparedness and response. There are no short cuts to clinical preparedness for EVD. These documents and their revisions should be reviewed carefully.

Multiple Circulating Infections Can Mimic the Early Stages of Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers and Possible Human Exposure to Filoviruses in Sierra Leone Prior to the 2014 Outbreak

Lassa fever (LF) is a severe viral hemorrhagic fever caused by Lassa virus (LASV). The LF program at the Kenema Government Hospital (KGH) in Eastern Sierra Leone currently provides diagnostic services and clinical care for more than 500 suspected LF cases per year. Nearly two-thirds of suspected LF patients presenting to the LF Ward test negative for either LASV antigen or anti-LASV immunoglobulin M (IgM), and therefore are considered to have a non-Lassa febrile illness (NLFI). The NLFI patients in this study were generally severely ill, which accounts for their high case fatality rate of 36%. The current studies were aimed at determining possible causes of severe febrile illnesses in non-LF cases presenting to the KGH, including possible involvement of filoviruses. A seroprevalence survey employing commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay tests revealed significant IgM and IgG reactivity against dengue virus, chikungunya virus, West Nile virus (WNV), Leptospira, and typhus. A polymerase chain reaction–based survey using sera from subjects with acute LF, evidence of prior LASV exposure, or NLFI revealed widespread infection with Plasmodium falciparum malaria in febrile patients. WNV RNA was detected in a subset of patients, and a 419 nt amplicon specific to filoviral L segment RNA was detected at low levels in a single patient. However, 22% of the patients presenting at the KGH between 2011 and 2014 who were included in this survey registered anti-Ebola virus (EBOV) IgG or IgM, suggesting prior exposure to this agent. The 2014 Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak is already the deadliest and most widely dispersed outbreak of its kind on record. Serological evidence reported here for possible human exposure to filoviruses in Sierra Leone prior to the current EVD outbreak supports genetic analysis that EBOV may have been present in West Africa for some time prior to the 2014 outbreak.

Clinical Illness and Outcomes in Patients with Ebola in Sierra Leone

Limited clinical and laboratory data are available on patients with Ebola virus disease (EVD). The Kenema Government Hospital in Sierra Leone, which had an existing infrastructure for research regarding viral hemorrhagic fever, has received and cared for patients with EVD since the beginning of the outbreak in Sierra Leone in May 2014.

Caring for Critically Ill Patients with Ebola Virus Disease. Perspectives from West Africa

The largest ever Ebola virus disease outbreak is ravaging West Africa. The constellation of little public health infrastructure, low levels of health literacy, limited acute care and infection prevention and control resources, densely populated areas, and a highly transmissible and lethal viral infection have led to thousands of confirmed, probable, or suspected cases thus far. Ebola virus disease is characterized by a febrile severe illness with profound gastrointestinal manifestations and is complicated by intravascular volume depletion, shock, profound electrolyte abnormalities, and organ dysfunction. Despite no proven Ebola virus–specific medical therapies, the potential effect of supportive care is great for a condition with high baseline mortality and one usually occurring in resource-constrained settings. With more personnel, basic monitoring, and supportive treatment, many of the sickest patients with Ebola virus disease do not need to die. Ebola virus disease represents an illness ready for a paradigm shift in care delivery and outcomes, and the profession of critical care medicine can and should be instrumental in helping this happen.

Lassa Fever in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone

Lassa fever (LF), an often-fatal hemorrhagic disease caused by Lassa virus (LASV), is a major public health threat in West Africa. When the violent civil conflict in Sierra Leone (1991 to 2002) ended, an international consortium assisted in restoration of the LF program at Kenema Government Hospital (KGH) in an area with the world's highest incidence of the disease.

Media Appearances

Ebola Survivors May Be the Key to Treatment—For Almost Any DiseaseEbola Survivors May Be the Key to Treatment—For Almost Any Disease

Eventually Moses returned to the US. But now, two months later, she and one of the people she'd worked with, a physician named John Schieffelin, were back. Moses' driver eased the Land Cruiser up to her old lab, a single-story building tucked in the corner of the hospital compound. Workers appeared and started to help unload supplies. Moses, meanwhile, stepped out into the searing midday heat and stretched her legs. She saw six people sitting on the concrete steps of an office across from her lab. Some had been nurses and researchers at Kenema; a couple were part of a newly formed survivors' union. That's how they'd heard about Moses' mission.

After Nearly Claiming His Life, Ebola Lurked in a Doctor's Eye

When Dr. Ian Crozier was released from Emory University ... the picture is much the same, according to Dr. John S. Schieffelin, ...

Exclusive: U.S. Ebola researchers plead for access to virus samples

Importing Ebola virus into the United States has always been tricky, said Dr. John Schieffelin of Tulane, who has treated Ebola patients in Sierra Leone.

Here's What Scientists Know About Ebola in Sierra Leone

The new records were a challenge to collect, since infection control rules meant that the paper charts could not be transferred back and forth between the ward where patients were treated and other areas of the hospital. “The nurses’ station was separated from the patient rooms by essentially a chicken wire window, so the nurses would talk to each other through the chicken wire—the nurse inside, in personal protective equipment, would tell the nurse outside what to write down,” says paper co-author Dr. John Schieffelin, an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics and internal medicine at Tulane University who has been serving stints at the hospital for the last four and a half years. Even that rudimentary system was state of the art for the region, where most health clinics do not keep medical records. “In most of Sierra Leone, the hospital chart is one of those little composition books that we used to write essays in during high school,” says Schieffelin. “There was no structure to it; the physician would just write daily notes and most hospitals don’t have a charting system.”

Ebola Healthcare Workers Are Dying Faster Than Their Patients

But between local workers, that same promise of care, while equally sincere, is less dependable. In Kenema, Sierra Leone, where Tulane professor Dr. John Schieffelin arrived under WHO to treat Ebola patients, each worker’s infection was a resounding blow to the local staff’s efforts not only to maintain care for patients, but also for each other.