Bruce Raeburn dispels Storyville myths

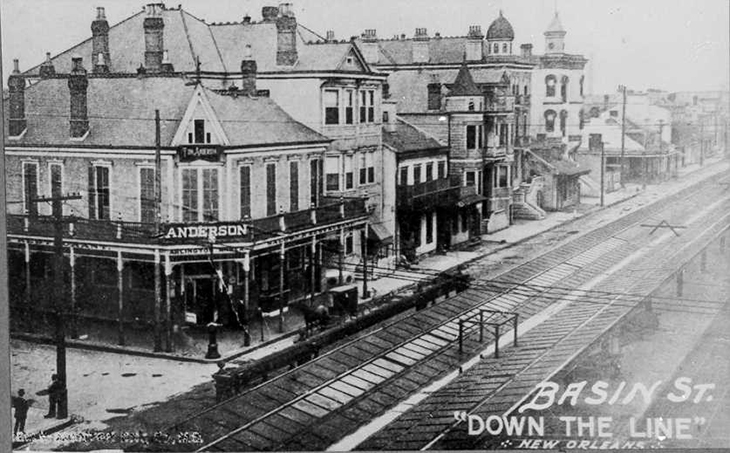

This 1910-era publicity postcard, “Basin Street "Down the Line,"” depicts the infamous Storyville District of New Orleans. (Image from the Hogan Jazz Archive, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library)

Do you know what it means to miss New Orleans? Louis Armstrong did, though according to Bruce Raeburn, perhaps not for the reasons that most people think.

Raeburn, curator of the Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University, spent the past year tracking the diaspora of New Orleans musicians from the city during the years from 1902â“1922. He gave a presentation on the topic at the Satchmo SummerFest in early August. The common explanation for the mass exodus of musicians is the closing of Storyville, the city"s infamous red light district, in November 1917.

“There"s a lot of mythology,” Raeburn says. “There are scholars who still believe that jazz was born in Storyville and that all the musicians left when the district closed. It"s a romantic idea.”

While Raeburn is not the first scholar to doubt the veracity of “the Storyville diaspora myth,” he is the first to actively research to dispel it.

“None of them have ever actually tracked all the musicians and subjected that issue to a micro-history approach,” he says.

To conduct such a research project requires investigating all forms of media and archival documents. Call him the Indiana Jones of Jones Hall, where he also is director of the Tulane Special Collections.

“You have to do some digging to really firm up the oral history that can otherwise be too ambiguous,” Raeburn says. “You have to draw on a very broad spectrum of material in order to pin down the historical issues.”

Trumpeter Armstrong ultimately followed his mentor, Joe Oliver, to Chicago on Aug. 8, 1922, and did not return to his hometown until 1931.

“Armstrong was a little bit more reticent, maybe more fearful, about the risks of leaving town,” Raeburn says. “Joe Oliver left because he felt he was being harassed by New Orleans police. He was arrested a few times for disturbing the peace while playing music.” Once Oliver was in Chicago, Armstrong felt better about leaving.

Like many other musicians of the period, he left to pursue better pay and working conditions, racial equality and safety not to seek out another Storyville.

Johanna Gretschel holds bachelor"s and master"s degrees from Tulane University. She is a freelance writer living in New Orleans.

“There are scholars who still believe that jazz was born in Storyville and that all the musicians left when the district closed. It's a romantic idea.” -- Bruce Raeburn, curator, Hogan Jazz Archive