The Color of Carnival

Mardi Gras in New Orleans is known internationally for its whimsical parades and rainbow-colored beads, yet beneath the surface of its festivities lies a history of race discrimination and gender inequality. Kevin Gotham, associate dean and author of Authentic New Orleans: Tourism, Culture and Race in the Big Easy, says that while Carnival has always been celebrated by all segments of society, exclusivity was strictly enforced in the krewes that came about in the 19th century.

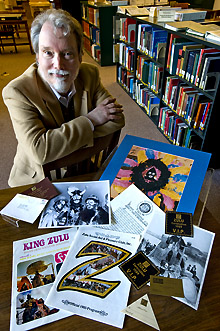

Programs, posters and photographs from the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club highlight the 100-year history of the Carnival organization formed by African Americans. (Photos by Paula Burch-Celentano)

Carnival masking in New Orleans dates back to the late 1700s, and though it was prohibited under Spanish colonial rule, it was again made legal in 1827. In 1857, the first Carnival krewe, Comus, staged a parade through the city streets. It was a segregated organization, as were the other “old line” krewes that followed Rex, Momus and Proteus.

Gotham, associate dean of academic affairs for the School of Liberal Arts and a sociologist, says that records of Carnival from the late 1800s indicate that crowds gathering to watch the parades often included Creoles and African Americans. Although racial discrimination ruled within local institutions, it was difficult to enforce and maintain segregation during parading.

“There is no indication that spectators were restricted because of race,” says Gotham. “But the distinct social clubs that moved Mardi Gras in the direction of what we see today were definitely comprised of members of the economic elite” at the time, primarily white males.

Eventually the exclusivity of krewe policy would become the catalyst for blacks and females to organize their own clubs.

Leon Miller, manuscripts librarian in Special Collections at Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, shows Zulu items that are part of the university's large Carnival collection.

“The events of Mardi Gras follow the trends of U.S. society,” says Gotham. “When we see the formation of early women's krewes it follows the rise of the women's suffrage movement, and the formation of early African American krewes comes alongside a resurgence of civil rights organizations.”

The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, which this year is celebrating its 100th anniversary, spent much of its early existence as a group spontaneously organized to parade on the back streets of New Orleans, as African Americans were legally barred from parading on the city's main thoroughfares.

It was not until 1968, nearly 70 years after the group began parading, that it would get the opportunity to join other krewes on more visible routes including St. Charles Avenue and Canal Street.

By the 1990s, Mardi Gras in New Orleans had blossomed into a major tourist attraction, but would face something of a crisis. In 1991, the New Orleans City Council voted unanimously to implement an anti-discrimination law prohibiting Carnival organizations, which enjoyed the use of public streets and facilities, from discriminating on the basis of race, color, sex, sexual orientation, national origin, ancestry, age, physical condition or disability.

After much public debate and acrimony, Gotham says that three of the krewes integral to Carnival's history, Comus, Momus, and Proteus, stopped parading. The Krewe of Proteus eventually resumed its annual Carnival appearance.

The city council later “softened the enforcement” by allowing krewes that were either all-male or all-female to remain as such. Although the krewes of Comus and Momus never returned, several more diverse krewes have been incorporated, and krewes such as Rex that existed before the anti-discrimination law have since made attempts to diversify their memberships.

“Despite all the problems, conflicts and struggles that have occurred with Carnival, the most important thing to note is its lasting power,” says Gotham. “It's an attraction that has been celebrated for about 200 years and it continues to serve as a cultural expression for the city.”