Environmental Cases Make History

In environmental circles, "Storm King" is shorthand for a landmark legal battle that served as a shot heard around the world. It's also the fitting title for the first chapter of a new book that tracks the confluence of historical, cultural and political circumstances integral to the movement of environmental litigation that has gone viral during the course of the last 50 years.

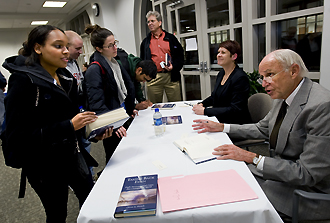

Environmentalist and law professor Oliver Houck, right, talks with fans at a booksigning event at the Tulane Law School. (Photo by Paula Burch-Celentano)

In Taking Back Eden: Eight Environmental Cases That Changed the World, Tulane law professor and environmentalist Oliver Houck tells the stories of citizens across the globe who accessed their countries' courts to defend their environment.

"These are very similar stories in very different dress," says Houck. "They all followed the same pattern a priceless resource and indomitable little group of people who banded together to protect it and then turned to the courts."

It all began in the early 1960s, with a utility company's proposal to build a hydroelectric plant at Storm King Mountain, located in the Hudson River Highlands just north of New York City. When locals wanting to protect the area's natural and cultural heritage joined with commercial and recreational fishermen in seeking judicial redress, they not only created a model for environmental activism but set a precedent for ordinary people to protect the environment through the legal process.

"Litigation created it, and litigation pushed it forward," says Houck, who portrays the efforts of concerned citizens in Japan, the Philippines, Canada, India, Russia, Greece and Chile in what amounts to a compelling and enthusiastic affirmation of what it means to "do good."

"Every border it traveled, [the environmental movement] ran into the same philosophical resistance that courts exist to protect private interests," says Houck. "Courts are really instruments of the power structure."

The cases presented in the book, however, were "bombshells" that changed the legal landscape by establishing what Houck calls the "revolutionary idea that citizens can enforce an environmental principle against their own governments."