Famed 1938 City Guide Still Pertinent Today

Subtle and elusive, New Orleans always has presented a challenge to those who want to tell its story. Few books have done the job as well as The 1938 New Orleans City Guide. First published by the Works Progress Administration, the volume still has value as a compendium of this most unusual city, as well as a window into the complex individual most responsible for compiling it, says Larry Powell, Tulane professor of history and author of the introduction to a recent republishing of the book.

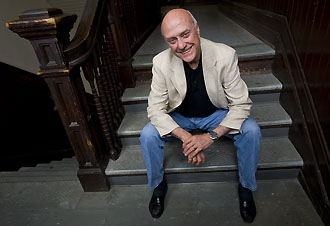

Tulane historian Larry Powell is the author of the introduction to the republished The 1938 New Orleans City Guide, which is still viewed as a remarkable view of New Orleans history and culture. (Photos by Paula Burch-Celentano)

“No guide before or since ⦠has done a better job mapping the Crescent City's fabled enjoyment culture,” writes Powell in the introduction.

“It surveys most of the city's music and art scene from that period ⦠and evokes New Orleans' love of fun and whimsy.”

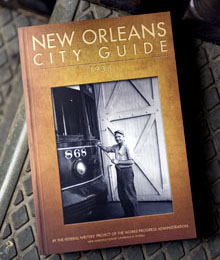

Garrett County Press republished the city guide, which features more than 54 sections in 455 pages, still holds up as a credible guide, despite its “antique point of view,” says Powell.

It originally was written and compiled by the Federal Writers' Project of the WPA, a program designed to provide work relief for artists and professionals during the Great Depression.

The project produced over a thousand books and pamphlets on local history, folkways and culture.

“A lot of what the book mentions is still in place,” he says. “Fortunately our conservativism has played in our favor because we haven't let the place be bulldozed as in other cities.”

In researching the guide's initial publication, Powell says he became fascinated with Lyle Saxon, the journalist, author and denizen of the French Quarter who was contracted to manage the project of producing the guide.

The Works Progress Administration's Federal Writers' Project published the original guide to provide work for artists during the Great Depression.

Saxon, interestingly, was one of the city's first preservationists, and it was his articles about the French Quarter that were not only key to keeping its historic cityscape intact, but also to attracting the community of writers and artists that would come to populate this “poor man's Paris.”

Powell, however, also sees Saxon as a tragic figure, one who was not comfortable in his own skin.

“He was a closeted gay,” says Powell. “I think people knew he was gay but he was always trying to deny it. He was also a frustrated and, as he saw it, a failed novelist.”

Though the conflicts within Saxon's personality would lead him to alcoholism and depression, they might also have led Saxon to imbue The 1938 Guide to New Orleans with its distinctive tone, particularly regarding issues of race.

“I found his sexual orientation to be key to explaining why he approached racial issues the way he did,” says Powell. “He was in some ways embarrassingly old-South paternalistic and yet very open and respectful of black institutions and black culture.”

It was that paradox that intrigued Powell. “That's why I delved into his biography. I wanted to know more about what made him tick.”