Historian Adderley Wins Book Prize

Africans in Trinidad and the Bahamas set free from slave ships by the British after the abolition of the slave trade in 1807 had certain rights and autonomy that enslaved people did not, says Rosanne Adderley, associate professor of history.

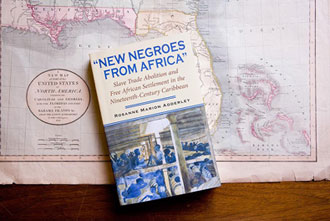

Roseanne Adderley, associate professor of history at Tulane, received the Wesley-Logan Prize in African Diaspora History in recognition of her book's high scholarly and literary merit. (Photo by George Long)

But that does not mean "in the least bit that they had uncomplicated lives," she adds.

In her book "New Negroes From Africa": Slave Trade Abolition and Free African Settlement in the Nineteenth-Century Caribbean, Adderley focuses on the experiences of the unusual group of approximately 15,000 rescued Africans who settled in the Caribbean British colonies.

Adderley has been awarded the Wesley-Logan Prize in African Diaspora History in recognition of the book's high scholarly and literary merit.

The prize is jointly sponsored by the American Historical Association the professional association of historians in the United States and the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

Adderley officially received the award at the American History Association's annual meeting in Washington, D.C., in January.

As a comparative African Diaspora historian, Adderley says, "It's nice to receive an award that is so specifically in your field and a field that is important to you."

More than 12 million Africans were transported across the ocean and enslaved in the Americas as part of the Atlantic slave trade in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

Overwhelmingly, stories of Africans in the Americas in this period are told through the prism of slavery.

Most North American audiences "are deeply conscious of the way in which enslavement did a kind of violence to African culture," says Adderley.

When the British began policing the illegal slave trade, they interdicted slave ships on the seas en route to the Americas. Approximately 150,000 Africans were "liberated" altogether. Most of them were transported to Sierra Leone in Africa, but approximately 10 percent ended up in the Caribbean.

When Adderley began her investigation of free Africans in the Caribbean, she says that she did not have a preconceived notion about how they engaged the world.

"I didn't need the story to come out in a particular way, or even expect it to," she says.

What she learned from diverse records and extensive research is that the liberated Africans remained African while they simultaneously became African American.

"They had it both waysor had it all ways," she says. "They worked all sides of the street."

They functioned with both African and western identities. Like most immigrants to the Americas, they assimilated into a new culture. But they also kept a "shared cultural, linguistic identity with people from similar parts of Africa to them."