Jewish Identity and Society

A new book by Tulane professor Brian Horiwitz offers a model of individuals and institutions struggling with a concern central to Jews in America and around the world how to retain a strong Jewish identity while fully integrating into modern society.

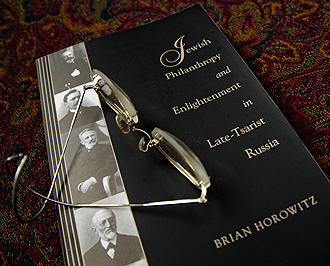

A new book by professor Brian Horowitz offers a model for Jews struggling with retaining a strong Jewish identity while integrating into society. (Photos by Paula Burch-Celentano)

Horowitz's Jewish Philanthropy and Enlightenment in Late-Tsarist Russia, published by the University of Washington Press in April 2009, focuses on the Society for the Promotion of Enlightenment (known by the acronym OPE) among the Jews of Russia. The philanthropic society that thrived in the late 19th century is the oldest Jewish organization in Russia.

In researching the book, he gained unprecedented access to the archives of the state historical society in Russia. Horowitz, who holds the Sizeler Family Chair of Jewish Studies at Tulane, had a yearlong fellowship in St. Petersburg, Russia. The chair of the Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies, he also is the author of The Myth of A. S. Pushkin in Russia's Silver Age.

“I stumbled upon an archive of Russian Jewry that was closed for a half century to everyone,” Horowitz says. “I was the first to touch this material in decades. I understood the importance of these people as leaders of Russian Jewry.”

The OPE was a secular, nonprofit society that was founded by a few wealthy Jews in St. Petersburg who wanted to improve opportunities for Jewish people in Russia by increasing their access to education and culture. When educational opportunities became closed to Jews, the society built a network of schools and libraries throughout Russia, opened a teacher training academy and a Jewish university, and held concerts and lectures. The OPE encountered opposition from the Russian government that imposed strict regulations on all aspects of Jewish life.

Horowitz's Jewish Philanthropy and Enlightenment in Late-Tsarist Russia (University of Washington Press, April 2009) focuses on a late 19th-century philanthropic society.

As Horowitz conducted the research for the book, the current government made it difficult for him. He was allowed to view the archival materials in a small room while an official watched over him.

The book corrects a popular misconception of Russian Jews in history solely as victims of pogroms and the oppressive laws imposed by the state. The Jewish leaders portrayed in the book create and foster a new Jewish identity based on traditional Jewish ideals such as ethics and philanthropy, combined with Russian ideals such as collectivism and self-sacrifice.

“They represent a unique type of personality found nowhere else in the world a Jewish identity that was a synthesis of the ideals of the Jewish tradition and virtues inspiring the attributes of the Russian worldview,” Horowitz says. “They believed Jews would be able to expand Jewish continuity and be partners with the liberal elements of Russian society who embodied these ideals.”

Although the experiment failed when the Bolsheviks came to power, Horowitz believes American Jews today can learn from the OPE's experiment.

“What remains is the idea and the attempt to blend together Jewish education with secular education,” Horowitz says. “We face a similar paradigm in America, with the loss of Jewish identity. The means to combat it is education. But that's not enough. Assimilation is inevitable in a free, multiethnic society. The only way one can engender Jewish identity is to have it be an important part of people's actual lives.”

With funding from the Posen Foundation, Horowitz will be teaching a freshman seminar on “Building Jewish Institutions” in the fall.