Telling the Whole Story

Mayor Jake Middleton calls his city of Natchez, Miss., the oldest on the Mississippi River, and its history has definitely been its calling card, with the city staging a biannual “pilgrimage” to dozens of antebellum mansions once owned by planters.

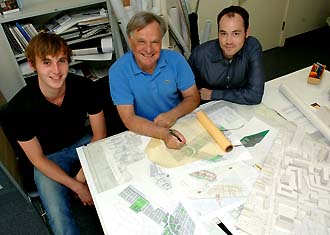

The team working on the Natchez, Miss., project includes, from left, architecture student Robert Bracken; Grover Mouton, director of the Tulane Regional Urban Design Center, and Nick Jenisch, project planner for the center. (Photo by Paula Burch-Celentano)

But there's a dark side to the history that played out in the fields of those plantations as well as on the city's outskirts, in a place known as the Forks of the Road, once the second-largest slave market in the Deep South. A proposed museum to slavery located on those historic grounds is the focus of a collaboration between Middleton, Natchez citizens and Grover Mouton of the Tulane School of Architecture.

While the largest slave market was in New Orleans, an estimated 300,000 slaves were sold in Natchez in a 12-year period that ended in 1863 when Union troops occupied the city, says Mouton, an adjunct associate professor who also is director of the Tulane Regional Urban Design Center. He calls the Forks of the Road “an extremely significant site in the history of America.”

At the peak of the Natchez market, as many as 500 slaves were present on any given day. Now, the only evidence of Forks of the Road is a marker at a three-road intersection.

If Mouton has his way, a high-tech interpretative center and museum will be built on the site, but several years of planning and fundraising must take place before his vision can be made a reality.

“We've been working on it for a year and a half, quietly,” Mouton said. His team at the Tulane Regional Urban Design Center developed a master plan for the project along with Natchez officials and secured a $500,000 allocation from the Mississippi Development Authority for the City of Natchez. Robert Bracken, a May graduate of the architecture school who is now part of the Tulane master of preservation studies program, worked on the design of what Mouton projected would be a $20 million project.

Recently, Mouton and Nick Jenisch, project director for the center, crafted a $40,000 National Endowment for the Arts Design Grant for the city. Jenisch also was Mouton's collaborator on the $500,000 MDA request.

While the larger Mississippi allocation is for construction, the NEA funds will allow the planning to move forward, even if the planners have to consider a smaller, phased-in approach to the work.

Robert Bracken, a May graduate of the architecture school who is now part of the Tulane master of preservation studies program, developed this preliminary design for the proposed Natchez museum.

“Grover has been a tremendous help to us, helping us procure monies to possibly get this thing really kicked off,” the Natchez mayor said. “Eventually we want to build some sort of facility or museum, and tell the whole story about the slave market, about Forks of the Road, from the beginning until the end.”

The project has special significance for Mouton, a Louisiana native who has led similar museum design projects, including work for the Birmingham Civil Rights District, for which he won a National Trust Honor Award in 1993.

By working with Natchez, Mouton said, “I believe that the university and the School (of Architecture), through the TRUDC, have substantially impacted the interpretation of this sad time in our history. It will be a Mississippi tourism and educational facility that will tell the rest of the story of pilgrimage and culture.”

Middleton is hopeful that the project will move forward, despite the nation's current financial crisis. His goal is to have the center under construction by the end of his mayoral term in three and one-half years.

The National Park Service currently is doing a boundary study of the Forks of the Road site, to determine the exact area that it covered. While the city already owns a portion of the site, additional land area may be needed for the full project.

“African American history is just as important to the city as other history,” Middleton said. “It's something that we want to make sure we do right when we do it. There were a lot of people that went through that part of our city. A lot of their ancestors may still be here.”