Tulane professors help students stay ahead of the class

Justice does not end with punishment. Knowledge differs from wisdom. Resilience is a way to resist shock.

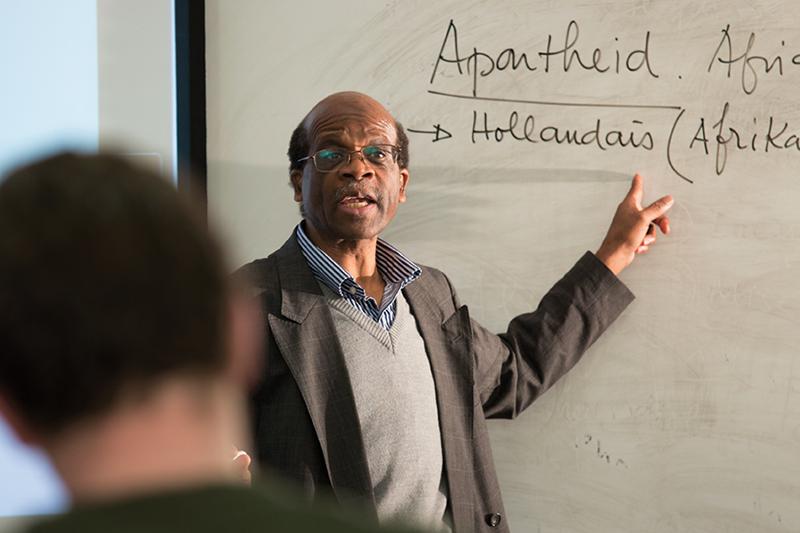

These are among the themes of Jean Godefroy Bidima’s courses in advanced French and philosophy of the self, society and institutions.

Sometimes at the end of class, he says, students come to him and say sincerely, “Oh, sir, I do thank you because when I entered your class, I did not know that. Now I know that, and what you taught me is not only to have a grade but it is how to behave as a member of our common humanity.”

“It’s exciting for me when I hear that students take concepts that they were taught in class and then bring them to other areas that they might be studying or thinking about or even to the decisions they make in daily life.”

— Mary Olson, associate professor of economics

Bidima is a professor of French and holder of the Yvonne Arnoult Chair in Francophone Studies. He is the author of Theorie Critique et Modernite Negro-Africaine: De l’Ecole de Francfort a la “Docta Spes Africana” (Publications de la Sorbonne, Paris, 1993), La Philosophie Negro-Africaine (Presses Universitaires de France, Paris, 1995), L’Art Negro-Africain (Presses Universitaires de France, Paris, 1997), La Palabre, une Juridiction de la Parole (Editions Michalon, Paris, 1997) and Law and the Public Sphere in Africa (Indiana University Press, 2013).

Adriana Amador is a student whose understanding of the world was changed by Bidima.

A second-year student on a pre-med track with a psychology major and French minor, from San Juan, Puerto Rico, Amador took Bidima’s class last spring. She says that before she always thought that justice was synonymous with law. However, Bidima changed her perspective on that—and everyone’s in the class. True justice is “more about reconciling with people after they are judged,” she says.

For his part, Bidima says, “That was my strategy on this course on justice. Justice is not to crush the individual. It is to redeem the person, to secure the community and enrich the institutions.”

The kind of exchange that happened between professor Bidima and his student Amador occurs in countless faculty-student interactions all over Tulane.

For a university to be truly great, it depends upon well-informed and caring teachers.

Tulane has many such teachers and has had for years—as thousands of graduates can attest.

To move forward, Tulane plans to continue to invest in its professors.

Phyllis Taylor, co-chair of “Only the Audacious,” said at December’s launch of the campaign, “With transformative teaching, Tulane inspires generations of young people to become creative thinkers and inspired doers.”

Taylor is the benefactor for her namesake center, The Phyllis M. Taylor Center for Social Innovation and Design Thinking at Tulane, where students learn by doing and where what is possible in the classroom is being redefined.

The campaign provides an opportunity “to set a new standard by investing in our creative and brilliant faculty,” Taylor said.

Mary Olson is among the hundreds of Tulane professors who transform students’ thinking and insight into how the world works.

An associate professor of economics, Olson is also a core faculty member in the Murphy Institute—an interdisciplinary program that connects economics, political science, political economy, philosophy and law.

Interdisciplinarity is important for generating interest and motivating students, she says. Olson views her job as trying to serve as a bridge to help students see new ideas and connections, to not look at things from narrow perspectives but to view the world more broadly.

A course needs to be well organized and have a logical flow with a good progression, she says. She takes an interactive approach to facilitate student learning.

“I want to engage students with the material,” she says. “I want them to feel like the classroom is a place where they can feel comfortable asking questions.”

Among the classes she teaches is Positive Political Economy, a required course for political economy majors. Here, students learn how economic theories, models and frameworks can be used to predict and explain political decision-making.

“I think the students find the material incredibly interesting,” she says.

The class studies real-world examples of problems associated with group choices in politics as well as the strategic behavior of candidates who are competing for political office and other “puzzles that people might not really understand,” like why “lots of people don’t vote and why groups in Congress have trouble working together.”

While the examples sometimes present highly charged topics such as healthcare reform, about which people often have strong opinions, Olson said the work of the class requires more than an opinion. “It requires work. It requires students to understand models of political behavior, the assumptions behind those models and predictions arising from the application of a model in a particular context.”

The class is “quite conceptual,” says Olson. “I do believe in challenging the students. That is key.”

Olson sets the bar high. That’s what Shahamat Uddin found out when he took Olson’s Positive Political Economy course during his first semester at Tulane.

Now a second-year student—and a political economy major—Uddin, from Roswell, Georgia, by way of Bangladesh, signed up for the class in which mainly junior and seniors were enrolled.

“I was ready for the challenge,” he says. To get through the class and do well, he went to every single one of Olson’s office hours, as well as every class.

“She pushed me through and made sure that I understood the material.”

Uddin says he was inspired by Olson’s diligence and compassion. “She cared not just about us getting good grades but about us learning the material. ”

Olson told the students, Uddin says, “I want you to know this material because you’ll be able to use or apply it well beyond this course.”

That attitude rather surprised Uddin. He now looks at his college education differently. “I came in thinking that I would spend four years here, get my diploma—get the piece of paper—and then go into a career and do exactly what I could have done before college.

“But professor Olson taught me that there are skills that we learn in college we can actually use beyond that.”

That comprehension gratifies Olson. “It’s exciting for me when I hear that students take concepts that they were taught in class and then bring them to other areas that they might be studying or thinking about or even to the decisions they make in daily life.”

Most students “rise to the occasion” in her classes, Olson says. “I see them evolve over the course of the semester.”

That they take the frameworks discussed and apply them in other contexts is what “I want to accomplish.”

The influence of Tulane professors often extends beyond the students to whom they teach academic subjects. In addition to their classroom roles, professors are mentors and advisers outside the classroom.

James Huck serves as a mentor to Posse Foundation Scholars. Posse Scholars—carefully selected and trained—are diverse and talented students who may be overlooked in the traditional college selection process. They are placed in supportive, multicultural teams—Posses—of 10 students, throughout their four-year undergraduate experience.

Huck, administrative assistant professor and assistant director of the Tulane Stone Center for Latin American Studies graduate programs, has been mentoring a Tulane cohort of Posse Scholars from Los Angeles for nearly three years.

In his mentoring role, he follows the same philosophy that he has developed in his teaching. “It’s a philosophy that doesn’t want to shut down students as agents of knowledge.”

This philosophy has evolved as he has had more contact with students over the years, he says. “I began to understand and respect that, even though I had more factual knowledge or theoretical training that was more substantive than what students brought to the table, students—especially students from backgrounds and experiences that were very different from mine—international students, students from marginalized communities—had important things to say that I hadn’t thought of before.

“I didn’t want to dismiss that. I thought it was valuable. That got me questioning, why haven’t I been exposed to this way of thinking?”

Huck recognizes that professors, even with their advanced degrees and training, are “not the final authority in knowledge production and creation.”

Rather, students “can be agents in the creation of knowledge.” This acknowledgement leads to students who are “more energized, engaged and excited about learning,” says Huck. The result is that he, as a teacher, is rewarded and challenged, too.

Anthonette Miller, one of Huck’s Posse mentees, credits him with always being there to “support, help, assist in any way possible” during her time as a student at Tulane. His advice and “listening ear” has been essential to her development, she says.

However, it’s a “two-way street,” she says. Teachers, like Huck, need to be able to communicate, “even though we come from different walks of life.”

Huck does that, Miller says. He listens—and she listens to him. “You don’t want a teacher that just wants to tell you things: ‘Well, this is how it’s supposed to be. It’s basically XYZ, and that’s the only way it goes.’”

Miller is in her third year at Tulane. She’s a public health major with her sights set on medical school. She’s dreamed of being a doctor her whole life. She started as a neuroscience major but after taking one public health course, she switched her major because, she says, “we have a generation of doctors who solely focus on treating the symptoms.”

She says that doctors need to learn to look beyond symptoms to the causes of illness, factors such as living conditions, socio-economic status, healthcare availability and nutrition.

“I think more students need to go to medical school through the public health perspective,” says Miller, who is on the maternal and child health track in her public health major.

She’s preparing to leave her imprint on the world. “Tulane has definitely expanded my view on the world and how I want to make a change in the world,” she says.

Before she changes the larger world, though, Miller is committed to changing Tulane. “I feel it’s important that we are always leaving a footprint no matter what we do.”

She’s involved in the Black Student Union and other campus organizations. She notes how the campus is diversifying more and more with each class. She wants to make changes on campus because “what you do affects those who come after you.”

Miller is definitely a success story, says Huck. “She’s blossomed at Tulane.”

That, he believes, is what transformative teaching is all about.

Editor's note: This story was originally published in the March 2018 issue of Tulane magazine.