Book examines Vietnamese community’s successful post-Katrina recovery

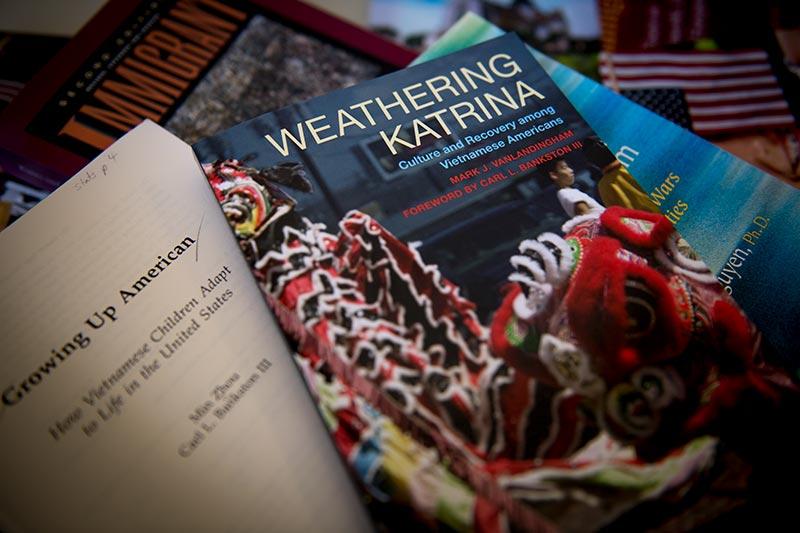

As the region became submerged in Hurricane Katrina’s floodwaters, the Vietnamese American enclave in eastern New Orleans was severely damaged. But this immigrant community followed the disaster with a stronger recovery than others that faced similar levels of flooding with similar levels of economic resources. In his new book Weathering Katrina: Culture and Recovery Among Vietnamese Americans, Tulane University professor Mark VanLandingham chronicles the group’s comeback, examining how their unique history acted as a catalyst for coping during crisis.

VanLandingham initially became interested in studying the population, which began settling in New Orleans after the collapse of the South Vietnamese government in 1975, after reading Growing Up American, a book coauthored by Tulane sociology professor Carl L. Bankston III.

Soon after arriving at Tulane two decades ago, VanLandingham and a team of Vietnamese graduate students and colleagues began a cross-national study comparing local Vietnamese residents with their counterparts living in Vietnam in terms of economic growth, mental and physical health and social connections.

“They’re a remarkable people and are an outstanding example of how immigrants provide vitality and inspiration to the rest of us in America.”

— Mark VanLandingham, Thomas C. Keller professor in global community health and behavioral sciences at Tulane University

“Just as I was finishing the data collection for the eastern New Orleans community sample, Hurricane Katrina hit,” he said.

VanLandingham evacuated from his flooded home to Texas.

“While I was there, it hit me that if I could re-interview these community members, then I’d have some predisaster data and be able to track their recovery over time,” he said.

The interviews VanLandingham conducted throughout 2006, 2007 and 2010 laid the groundwork for the book.

VanLandingham says that an opportunity in 2013 to spend a sabbatical year at the Russell Sage Foundation in New York City to write a first draft was also critical for pulling data together and for becoming familiar with the vast social science literature relevant to disasters.

Covering factors like health, housing and economic stability, VanLandingham’s interviews and longitudinal survey data formed the basis of his conclusion that the group fared much better than other devastated local communities during their rebuilding process.

In the second part of the book, he tackles the more difficult question: why?

VanLandingham found that the Vietnamese had a wide range of attributes that became advantageous during their recovery process. Sharing a history of starting over in New Orleans after fleeing South Vietnam, the group developed a culture that emphasized insularity, collective perseverance and progress.

Several non-cultural advantages played important roles as well. For example, the large building housing the Mary Queen of Vietnam Church became a central location where community members could gather to distribute supplies and to map strategy.

“They’re a remarkable people and are an outstanding example of how immigrants provide vitality and inspiration to the rest of us in America,” said VanLandingham.

Like this article? Keep reading: New Orleans schools remain as segregated as before Katrina