Tulane study shows COVID-19’s lingering impacts on the brain

COVID-19 patients commonly report having headaches, confusion and other neurological symptoms, but doctors don’t fully understand how the disease targets the brain during infection.

Now, researchers at Tulane University have shown in detail how COVID-19 affects the central nervous system, according to a new study published in Nature Communications. The findings are the first comprehensive assessment of neuropathology associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a nonhuman primate model.

The research team found severe brain inflammation and injury consistent with reduced blood flow or oxygen to the brain, including neuron damage and death. Microhemorrhages, or small bleeds in the brain, were also present.

Surprisingly, these findings were seen in subjects that did not experience severe respiratory disease from the virus.

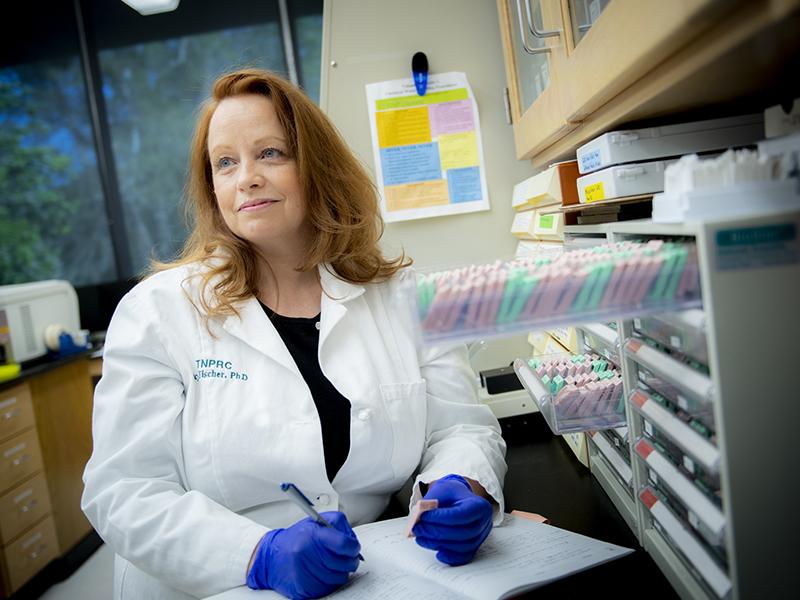

Tracy Fischer, Ph.D., lead investigator and associate professor of microbiology and immunology at the Tulane National Primate Research Center, has studied brains for decades. Soon after the primate center launched its COVID-19 pilot program in the spring of 2020, Fischer began studying the brain tissue of several subjects that had been infected.

Fischer’s initial findings documenting the extent of damage seen in the brain due to SARS-CoV-2 infection were so striking that she spent the next year further refining the study controls to ensure that the results she reported were clearly attributable to the infection.

“Because the subjects didn’t experience significant respiratory symptoms, no one expected them to have the severity of disease that we found in the brain,” Fischer said. “But the findings were distinct and profound, and undeniably a result of the infection.”

The findings are also consistent with autopsy studies of people who have died of COVID-19, suggesting that nonhuman primates may serve as an appropriate model, or proxy, for how humans experience the disease.

Neurological complications are often among the first symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection and can be the most severe and persistent. They also affect people indiscriminately — all ages, with and without comorbidities, and with varying degrees of disease severity.

Fischer hopes that this and future studies that investigate how SARS-CoV-2 affects the brain will contribute to the understanding and treatment of patients suffering from the neurological consequences of COVID-19 and long COVID.

The COVID-19 pilot research program at the Tulane National Primate Research Center was supported by funds made possible by the National Institutes of Health Office of Research Infrastructure Program, Tulane University and Fast Grants.