Tulane faculty, special guests give brief history on Black and Indigenous roots of Carnival, Mardi Gras Indians

Tulane’s ALAAMEA Alliance (Asian, Latino, African American, Multi-Ethnic, and LGBTIQ Alliance) recently explored the Black and Indigenous roots of New Orleans Mardi Gras in a virtual session for faculty and staff that combined musical performances and historical context.

In “Learning About Black and Indigenous Roots of Carnival Culture in New Orleans,” panelist Laura Rosanne Adderley, associate professor in the Department of History at the School of Liberal Arts, gave a brief history and framework of the interactions of African Americans and Native Americans/Indigenous peoples and how they are connected to Carnival and Mardi Gras Indians.

The history is rooted in serious subject matter, even though the celebration that we know as Mardi Gras is lighthearted.

Adderley prefaced her remarks by saying that she and a colleague often say that “our job, basically, as historians, is to ruin Mardi Gras for people.”

“It’s because there’s two things that are true about New Orleans Mardi Gras: It would not have shaped out the way it did, without the horror that African slavery was — a lot of stuff that we now consider beautiful and interesting.” The second thing, Adderley said, is that the city leadership that formed Mardi Gras into a formal festival season with organized krewes in the late 1800s or early 1900s was at one point involved in the oppression of Black and Indigenous people.

“There’s not a single white leader who helped found what we know as this Mardi Gras season, who wasn’t either deeply involved in or looking the other way to something pretty awful,” Adderley added.

Of the emergence of today’s Mardi Gras Indian tribes, Adderley said that African Americans and Native Americans had been interacting with one another since Europeans arrived in the Americas.

“You have in the Americas … Europeans invading, disturbing ancient Native American cultures and dragging along millions of Africans to work for them,” she said. By the time New Orleans was founded, years of “European invasion and practice,” had taken place. Once slavery was established, African Americans who fled slavery into lands that were occupied by Native Americans became permanent runaways among Native Americans.

Native Americans and African Americans also interacted during the 1800s when the United States was expanding and displacing Native Americans, taking over parts of the Great Plains in the West. At this time, African Americans were consuming the same information and culture and resistance to colonialism.

“Separate from these kind of everyday relationships under slavery (at the time), African Americans themselves also studied and paid attention to Native Americans and Native American resistance.”

Adderley added that Mardi Gras is also a celebration with Roman Catholic origins. “You have these exquisite Native American and African influence festivals all over the Americas that happen around Roman Catholic holidays.”

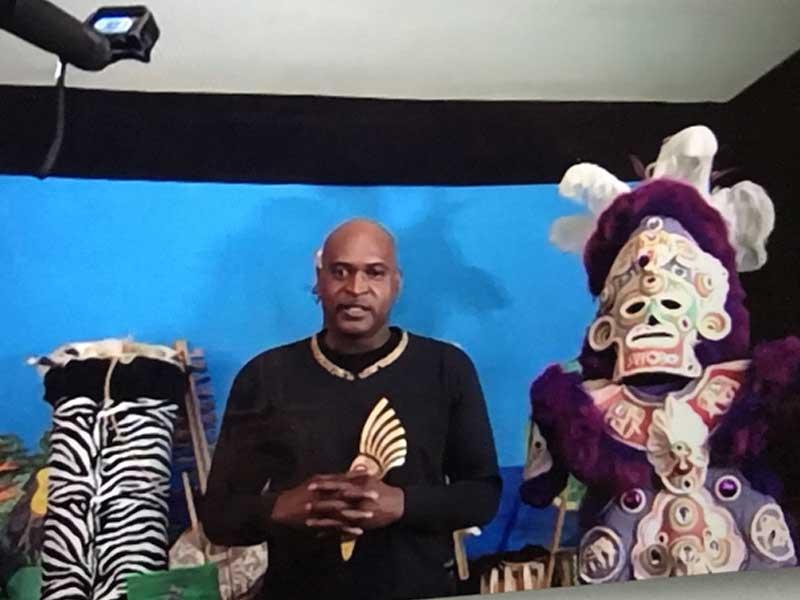

Co-moderator Carolyn Barber-Pierre then turned the session over to Chief Shaka Zulu, Black masking Indian/Mardi Gras Indian and co-owner of The Golden Feather Mardi Gras Indian Gallery. He was recognized as the first to mask in a Mardi Gras stilt dance.

Shaka Zulu, who has been immersed in Mardi Gras Indian culture since birth and masking for over 20 years, said, “Once you travel the continent of Africa, you’ll realize very quickly that New Orleans culture is very much African culture,” he said. He noted that many Africans were already in what is now known as Louisiana and New Orleans before the transatlantic slave trade.

However, when Europeans did arrive to the city, “most of the Carnival traditions, as we know, the African traditions, came out of what we call Congo Square.” (Congo Square, now located on North Rampart in Louis Armstrong Park, was a gathering place for Africans, many of whom were enslaved, where they could meet on Sundays).

Shaka Zulu pointed out that the term “Mardi Gras Indians” has stuck through the years. However, Mardi Gras Indians were not always allowed to celebrate with Europeans.

Instead, they masked against one another around Catholic observances such as Mardi Gras and St. Joseph’s Day.

The ALAAMEA session also included a welcome from co-moderator Anneliese Singh, chief diversity officer and associate provost of faculty development and diversity; a blessing in the Kaqchikel and Tunica languages from Judith Maxwell, professor in the Department of Anthropology at the School of Liberal Arts; and a special video performance by the One Shot Brass Band dedicated to university faculty and staff.

The pandemic prevented typical Carnival masking and gathering this year — even disrupting shipments of the fabric and supplies that the Mardi Gras Indians use to make their suits, which often take a year of hand sewing and beading to create. Still, Shaka Zulu said that New Orleanians remain the “culture keepers” of these traditions.

“You put all this stuff together to make this beautiful gumbo,” Shaka Zulu said.