The meeting of a lifetime: How two Tulanians forged a life and lasting legacy together

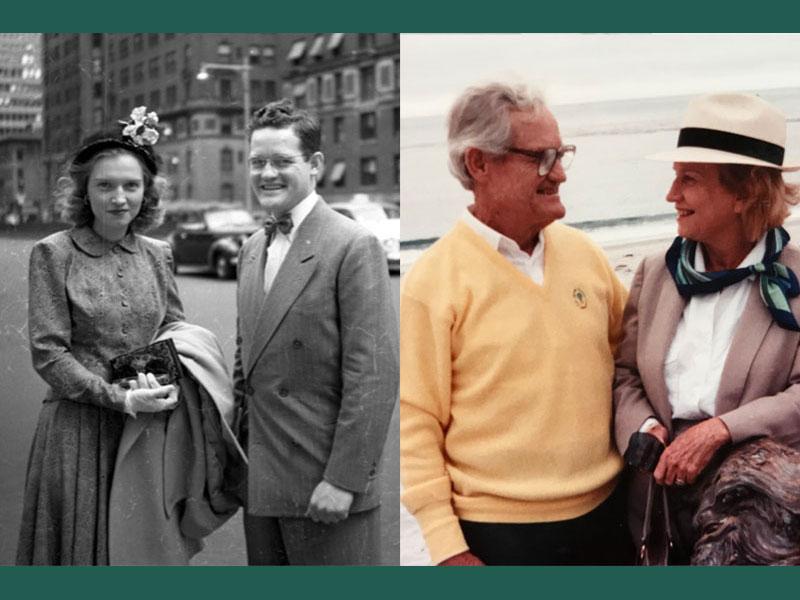

The chance meeting of a pair of Tulane University students at a medical school fraternity party almost 75 years ago led to a life filled with family, service and a lasting legacy that will continue at Tulane for years to come.

Barely into her first week at Tulane in the fall of 1946, Lenore Benson Raborn (SW `47) met Robert Raborn (M `48, R `52). The two fell in love, were married for 52 years and raised three children- Richard, Robin and Doug.

In 1974, the Raborns set up a trust for the benefit of Tulane valued at $750,000. In 1999, Robert passed away at the age of 76. The remainder of the now $1.925 million trust will eventually go to the couple’s alma mater, including 60 percent to the School of Medicine and 40 percent to the School of Social Work. But it all goes back to that first meeting.

“A major component of a Tulane education is bringing the greatest minds from different fields together to discover solutions and innovations,” Tulane President Michael Fitts said. “Occasionally, we also bring the greatest of hearts together. This seems to be the case with the Raborns and their lifelong love for one another, for Tulane and for the fields of medicine and social work.”

“My parents met at Tulane, where dad was in medical school, and my mother was working toward a master’s degree in medical social work,” daughter Robin Raborn said. “After they became engaged, they discovered that their mothers, Grace Kent Raborn and Laura Quayle Benson, had been roommates for two years at the Florida State College for Women.”

Robert Raborn took a bit of a circuitous route to Tulane Medical School with a little prompting from Uncle Sam.

“My father majored in agriculture at the University of Florida in Gainesville, which was only for men when he attended,” said son Dr. Richard Raborn, who also did his residency at Tulane. “He knew his family did not have money to send him to medical school, so he took additional science courses while pursuing agriculture. The U.S. Army drafted him out of college before he graduated and sent him to Tulane Medical School. It was World War II, and America needed doctors.”

Lenore and Robert were married in July 1947. Following four years of medical school and the completion of his internal medicine residency at Tulane, the couple settled in Washington, D.C., where Robert worked in the United States Public Health Service while Lenore was also doing public health with polio children victims.

Robert became the physician-in-charge at the U.S. Department of the Treasury, which included the uniformed Secret Service, during the Korean War in Washington, D.C. Lenore worked at the polio camp at former President Roosevelt’s retreat known as Shangri-La. They would walk around the area now known as Camp David.

“The future gift from the Raborn family will have a significant and lasting impact on the School of Medicine,” said Lee Hamm, dean of the School of Medicine and senior vice president. “I am grateful to Lenore Raborn and her late husband, Dr. Robert Raborn, for their generosity and support. The gift is all the more special because of the remarkable character of the donors.”

“The Tulane School of Social Work is humbled by the kindness and generosity of our alumna Mrs. Lenore Raborn and family,” said Patrick Bordnick, dean of the School of Social Work. “This gift will provide opportunities for the school to increase our impact by doing work that matters, both in our community and across the globe.”

The Raborns moved to Florida in 1954, where both Robert and Lenore proved to be trailblazers in their own ways. They each took on active roles in public health and voluntary service to those in need and the community as a whole.

Robert, a second-generation Florida physician, was a pioneer in the use of technology and medicine. He was a charter member and past president of the Bethesda Memorial Hospital medical staff, a hospital he helped found in 1959 in Boynton Beach, Florida. Robert was one of the first physicians to incorporate the use of satellite broadcast and videotape recorders into medical education at a time when technologies were in their infancy.

Lenore used her medical social work background and worked professionally in New Orleans to help Robert pay for medical school. When they moved back to her hometown in Florida, she worked as a volunteer in many organizations, often leading the local chapters.

“’Be the hands of God on Earth’ is my mother’s saying. We were taught to be medical social workers as she was trained by Tulane. This meant visiting people in nursing homes and learning from their life experiences. When I would come home from school in my teens, I remember my mother asking, ‘Well, what have you done today for the good of the world?’ My mother was a medical social worker all her life, far beyond the years it was her paid profession,” Robin Raborn said.